#2 Ship Manoeuvring - for rescue of person overboard

Ship Manoeuvres for a Man Overboard

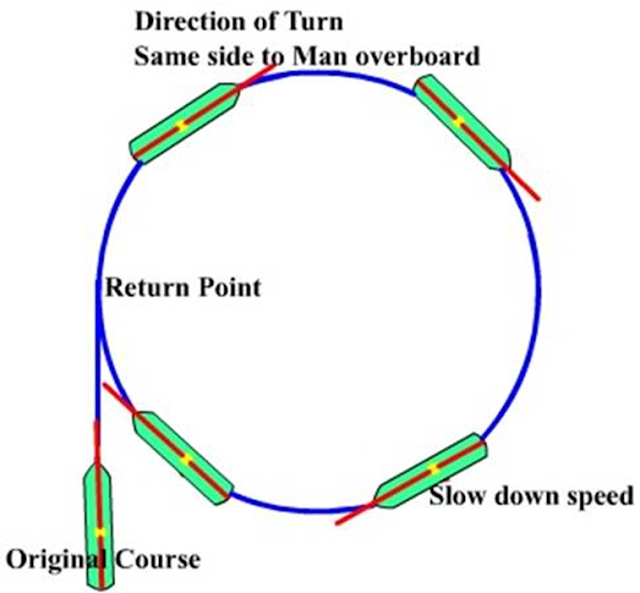

The Round or Anderson Turn is a maneuver used to

bring a ship or boat back to a point it previously passed through, often for

the purpose of recovering a man overboard.

This turn is most appropriate when the point to be

reached remains clearly visible. Both will require more time before returning

to the point in question.

1. If the turn is in response to a man overboard,

stop the engines.

2. Put the rudder over full. If in response to a

man overboard, put the rudder toward the person (e.g., if the person

fell over the starboard side, put the rudder over full to starboard).

3. When clear of the person, go all ahead full,

still using full rudder.

4. After deviating from the original course by

about 240 degrees (about 2/3 of a complete circle), back the engines 2/3 or

full.

5. Stop the engines when the target point is 15

degrees off the bow. Ease the rudder and back the engines as required.

If dealing with a man overboard, always bring the

vessel upwind of the person. Stop the vessel in the water with the person well

forward of the propellers.

The Williamson Turn

John A. Williamson entered the US Navy as a seaman

and later became the Commanding Officer of the USS England. As an instructor

ashore, Williamson developed a series of turns used to bring a ship back on its

own wake after a man fell overboard. Williamson recommended they

teach the turn as a maneuver for man overboard recoveries during night and low

visibility conditions.

Williamson after retirement wrote, “I’ve gotten

letters and seen articles where people have been picked up using (the turn). I

don’t have a clue as to how many. I don’t know whether it’s ten or 5,000. I

don’t feel that there’s any glory to me though. It’s just something I came up

with that turned out to be worthwhile. I don’t think I’m due any glory for it,

or any fame or anything like that.”

The principle behind the “Williamson Turn” is to return a ship to the

exact location where a seaman fell overboard by using the ship’s wake as a

reference point. This requires that a ship first turn to starboard, followed by

a turn to port that is concluded when the ship crosses its own wake.

This is the most efficient of all the turns till

date.

The manoeuvre basically comprises of the following

helm movements:

A wheel over of hard over on any side suitable

To maintain the helm until the course has altered

by 60 degrees.

Once this is achieved the wheel is put hard over on

the opposite side

The wheel is kept at hard over until about 20

degrees remain to bring the vessel to the reverse of original course, when the

helm is put to amidships

Helm is used to ease the ship on to the reverse

course. (It helps if the original wake of the ship can be seen)

This is the most efficient since without any

navigational aid the ship would retrace her path and go up the course line.

Small deviations are to be allowed for the tide and

current and wind effects. But overall is the best method to recover or to at

least go over the path of the ship.

The above plot is an actual done on board a medium

sized tanker and as can be seen there is very small deviation. Of course the

positions were plotted by GPS fixes. But the position fixing was superfluous.

(MOB position: Lat. 16˚36.2’N, Long. 082˚47.65’E)

Regarding which side to put the wheel over the

first time, a lot has been said about putting the wheel over on the same side

as the man overboard.

Actually the amount of time it takes for a man

floating to pass the stern and the time it takes to raise the alarm and

actually to put the helm over is so vastly different that the man overboard is

very far behind the ship by the time the ship starts turning.

Please note in the case of any turning of the ship

to recover a man overboard – it is assumed that the vessel is at sea speed.

Since at a anchorage/ harbour the lowering of the lifeboat is much

more convenient.

The Scharnow Turn

The Scharnow Turn is a maneuver used to bring a

ship back to a point it previously passed through, often for the purpose of

recovering a man overboard.

The Scharnow Turn is most appropriate when the

point to be reached is significantly further astern than the vessel’s turning

radius. For other situations, an Anderson turn or a Williamson turn might be

more appropriate.

Put the rudder over hard. If in response to a man

overboard, put the rudder toward the person (e.g., if the person fell

over the starboard side, put the rudder over hard to starboard).

After deviating from the original course by about

240 degrees, shift the rudder hard to the opposite side.

When heading about 20 degrees short of the

reciprocal course, put the rudder amidships so that vessel will turn onto the

reciprocal course.

If dealing with a man overboard, always bring the

vessel upwind of the person. Stop the vessel in the water with the person well

forward of the propellers.

NOTE: All of the above turns to rescue a person

fallen overboard, the point to keep in mind is that the turns of every ship

differs from the theory. Together with the current and wind the ship may not be

actually over the position as required. As such a good look out – enough

commonsense as to the drift and that a small head in a vast ocean with waves is

very difficult to see. Even with the ship having retraced the path it may not

always be possible to see a small head in the waters. The MOB marker may drift

not always at the same rate as that of the person. SO good look out is very

essential and good common seamanship.

Sequence of actions to

take when a person is seen to fall overboard

Throw a Life Buoy with a self-igniting light

towards the person in the water.

Send a lookout aft.

Rush to the manual call button and ring the alarm

bell.

If a telephone or hand held radio is accessible

then inform the Bridge watch-keeping officer

If above not available then go up on the bridge and

inform the watch-keeping officer. Information should be as to which side the

person fell and his identity.

Actions to take when a man-overboard report is received on the bridge

Assume that you are the watch keeper:

Put the helm on the same side to the person in the

water

Throw down the Man overboard marker

Post a look out astern with binoculars

Note down the position of the ship by all possible

means

Ring standby to the engine

Inform the Master

Ring the alarm bell for Emergency

Inform on the PA system that this is not a drill

and that a person has fallen overboard.

Note down the wind direction and study the current

direction

Ask for the rescue boat to be prepared

Depending on the instructions as laid down by the

Master commence the Williamson turn

Once you see the MOB marker astern or if the

original wake is noticeable, bring the vessel back on course

Inform all ships in the vicinity of the incident

and send out a distress message

Once the vessel is on reciprocal course and the

engines are ready for manoeuvring

Slow down and if the marker is visible head for it.

When very close to the MOB, stop engines and lower

the RB.

Control measure

Select the appropriate firefighting technique: Fires on board vessels

This control

measure should be read in conjunction with Select the appropriate firefighting

technique

CONTROL

MEASURE KNOWLEDGE

To uphold the importance of

firefighter safety it is important to ensure information is gathered from all

available sources before deciding on the tactics for firefighting. Depending on

the location, type, size and severity of a fire on board a vessel, several

tactics are available to the incident commander.

Ship firefighting and incident

planning considerations should consider that any single compartment, multiple

compartments or primary containment boundary should be assessed from all six

sides of the cube where physically possible.

This may also include any preplanning

for Site-Specific Risk Information incident plans where there is a foreseeable

risk from cargo operations, roll-on-roll-off-passenger (RoPax) ship and ferry

operations, cruise terminals, etc. Where such plans exist, the incident

commander should take appropriate time to re-evaluate the assumptions and

tactics within the plan to ensure they are fit for the incident they are

dealing with.

If a dedicated UK fire and rescue

marine response (FRMR) team are handing this incident to a shore-side fire and

rescue service, then the following terms may be used to describe the strategy

and tactics employed:

Contained

The fire is extinguished or held

within an area or compartment (on all six sides) by elements of construction

(preferably fire-resisting), preventing immediate spread or endangerment of the

vessel

Maintained

The fire is 'contained' and resources

are sufficient to 'maintain' that containment through firefighting actions

(cooling, starvation, vertical ventilation or flooding)

Uncontained

The fire has breached fire resistant

construction or is burning freely, but has the potential to be 'contained', by

additional fire resistant structures, firefighting action, boundary cooling,

ventilation or fire protection systems

Uncontainable

The fire has developed to a stage

where it is not possible to hold heat and products of combustion within a

fire-resistant compartment with the resources available and uncontrolled spread

will inevitably threaten vessel safety

Firefighting options

·

Using the vessel's fixed

installations

·

Boundary cooling

·

Boundary starvation

·

Compartment flooding

·

Temperature monitoring strategy

·

Compartment smothering via lock

down/starvation

Consideration should be given to the

effects of sealing the compartment and monitoring the adjacent bulkheads/decks

and deck heads.

·

Committing fire and rescue service

personnel equipped with conventional hose lines, branches and breathing

apparatus to a compartment involved in the fire

·

Foam application

For further information on

firefighting methods refer to National Operational Guidance: Fires and

firefighting - Select the correct firefighting

technique

STRATEGIC

ACTIONS

Fire and rescue services should:

·

Have policies and procedures for

dealing with fires involving vessels, where there is an anticipated risk

TACTICAL

ACTIONS

Incident commanders should:

·

Liaise with the vessel's personnel

regarding the availability of fixed installations and suppression systems

·

Develop an intervention strategy

appropriate to current situational awareness and predicted fire development

·

Consider compartment boundary

cooling, starvation or flooding as a strategy

·

Manage the vessel's ventilation

systems in conjunction with the vessel's personnel

· Carry out an analytical risk assessment to support the decision to re-open sealed fire compartments

this is indeed informative and detailed... looking forward to your future industry related blogs-PP

ReplyDelete